TGVP Report - Humanoid Robots in 2025

Humanoid Robots in 2025 – Five Observations Behind the Headlines

Written by By Jingjie(JJ) Li and Shashank Mahajan (Kellogg MBA ‘26)

2025 has been a buzzy year for robotics. As attention shifts from large language models to physical AI, the sector has attracted surging interest from both the public and venture capital. Morgan Stanley predicts that Humanoid Robots will become a $5T market by 2050 and that growth in this domain is inevitable [1]. Robotics startups raised more than US $6 billion in the first seven months of 2025 alone [2].

But how aligned is the current user demand, and what are key players doing to maintain this momentum?

Figure 03, as reported by TIME, marks a clear break from the struggles seen in Figure 02 as recently as August ’25. The latest demos show the robot tackling far more intricate, human-like tasks including folding laundry, manipulating soft materials, and coordinating fingers and joints with precision [3]. Companies are no longer just demonstrating that robots can dance or run fast. They are doubling down on the precision and fine-motor control that actually matter in real household and workplace settings.

While 2025 was a buzzy year for robotics, it also signaled the start of real-world utility. Beyond the headlines, five specific trends emerged that captured early attention this year and are poised for significant growth in 2026.

Observation One: Next-Generation Robotics Are Systems – Not Just Software or Hardware

Prior to 2025, the prevailing belief was that advanced AI (the robot's brain) was the only differentiator that mattered. But as actual deployments begin, it’s becoming increasingly clear that this is far from a simple software play. Even the most sophisticated foundation models are limited by mechanical constraints. Without high-bandwidth actuators and resilient joints, the 'smartest' software remains clumsy in the physical world.

Hardware is quietly growing fast, and builders are finally breaking the old rules. In recent years, we’ve seen massive improvements in the motors and joints that move these robots. They aren’t just trying to copy human hands anymore. They are becoming superhuman, capable of bending and twisting in ways our own bodies simply can't.

Daxo Robotics is one such example, designing robot hands whose joint ranges and fine-motor flexibility surpass human anatomical limits. By using a sophisticated array of motors and soft-robotics principles, they are building hands capable of high-precision manipulation for manufacturing and lab automation. Their approach diverges from traditional actuation methods and shows just how much innovation is happening on the hardware side of robotics.

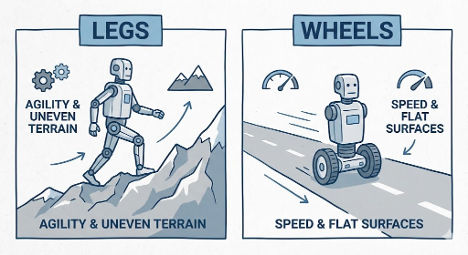

Observation Two: Legs vs. Wheels Argument

In theory, humanoid robots should adapt to the world, not the other way around. Since our cities and homes are built for walking, bipedal robots hold a distinct advantage in unstructured environments.

For decades, balancing on two legs was too slow and expensive. That has changed in 2025. Heavy hydraulics have given way to snappy, high-torque electric actuators, while AI models trained in simulation now give robots an almost continuous, reflex-like understanding of their balance. This allows them to handle stairs and clutter with agility that was impossible just a few years ago.

While some startups advocate for wheeled bases to save energy, this approach hits a wall. Wheeled robots struggle with the "last inch" of the physical world. A stray cable, a steep ramp, or a gap in the elevator floor can paralyze a wheeled machine. Legs treat these obstacles as stepping stones; wheels treat them as barriers. Unless we plan to repave our interiors to match the smoothness of a warehouse, legs remain the only form factor capable of true universal mobility.

However, the debate shouldn't be about which form is 'better,' but which is 'right' for the job. We advocate for a function-first philosophy: if wheels are enough, legs are unnecessary overhead. But if the terrain demands it, we shouldn't hesitate to build robots with three legs, four legs, or even eight like an octopus. The ultimate metric of a robot's success is its ability to complete tasks efficiently. We must define robots by their utility, not limit them to a specific shape

For example, Dexmate’s humanoids take the wheeled approach, pairing it with a foldable chassis that allows floor-level manipulation and extended reach. With higher energy efficiency and longer battery life, wheeled humanoids offer real advantages in their use cases.

Observation Three: Real-world Data vs Synthetic Data

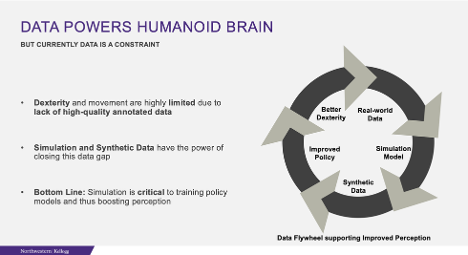

Much like the Foundation Models that power the chatbots we use daily, humanoid robots require a foundational model to guide their performance. However, unlike the massive text datasets used to train language models, there are constraints on the availability of data required to train Policy Models.

How do robots really learn? They can learn by doing (imitation learning) or by watching videos of humans performing tasks. While countless online videos could theoretically teach robots perception and manipulation, the data quality, consistency, and annotation requirements make this approach extremely challenging.

Gathering physical data in the real world to train policy models would take hundreds of years. To solve this, roboticists are turning to synthetic data.

Simulation takes a single dataset or demonstration and extrapolates it into millions of scenario variations: different lighting, object shapes, camera angles, friction values, disturbances, and failures. The robot learns to handle all of them, over and over, at accelerated speeds. This is how modern humanoids acquire the “common sense” of action.

But how do we trust the simulation?

To ensure the quality of this Sim-to-Real transfer, 2025 has seen a surge in rigorous academic benchmarking. New research like REALM (released late 2025) has moved the industry beyond simple success rates, introducing "Sim-vs-Real Correlation" metrics. This proves that a simulator is a valid predictor of reality, giving engineers mathematical confidence that if a model improves in the virtual world, it will improve in the physical one. Similarly, RobotArena has pioneered the use of AI to auto-generate "Digital Twins" from video, allowing robots to be benchmarked in thousands of messy, real-world environments

Startups like Duality are working in the autonomy simulation space to build data that is physically and semantically realistic, and predictive of real-world outcomes. SceniX, on the other hand, is taking a hybrid approach to simulation. They use a data flywheel that doesn’t end at synthetic data generation, but rather enriches their policy model with real-world data gathered from deployed policies. This not only enables low-cost data collection but also accelerates iteration cycles.

Observation Four: Rise of VLA (Visual Language Action) Models

We are all familiar with VLMs. They don’t just identify an object type (e.g., a mug), they also provide human context (e.g., distinguishing between a glass mug and a ceramic mug).

However, VLMs cannot perform object manipulations. This brings us to the ‘Action’ part: the Policy model. The VLA deciphers instructions produced by the VLM and translates them into physical execution such as desired wrist poses, finger flexion, and torso orientation.

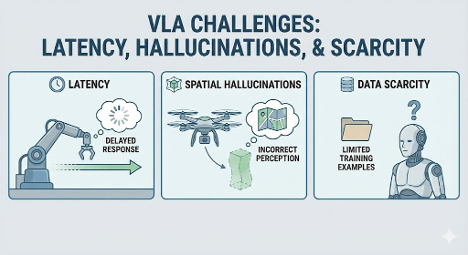

Bridging this gap is harder than it looks. In 2025, engineers are battling three major bottlenecks:

- Latency: A VLA might take 500ms to "think," but a robot falling over needs to react in 10ms. Running these massive models in a real-time control loop is a massive computational challenge.

- Spatial Hallucinations: A model might know what a glass mug is, but fail to know exactly where it is in 3D space. If the VLA is off by a millimeter, the robot crushes the glass instead of holding it.

- Data Scarcity: The internet is full of text and images, but starved of "Action Data"

Regarding deployment, Figure 03’s performance has been enabled by VLA. Figure does an excellent job explaining this while detailing how they built their tech stack (called Helix) around it. Similarly, 1X uses a VLA-based tech stack they call Redwood.

While humanoids are the poster child for this technology, we think 2026 will see VLA models break free for all physical assets.

We are already seeing early signs of this divergence. In late 2025, researchers introduced "Aerial VLAs", allowing drones to process natural language commands like "find the lost hiker near the red cliff" and translate them directly into flight trajectories without manual piloting. Similarly, automotive leaders like XPeng have begun testing VLA-based autonomous driving, where the car doesn't just "detect lanes" but understands semantic context, such as knowing that a waving police officer overrides a green light.

Observation Five: The overlooked Soft Side of Hard Robots

With pre-orders now rolling out for 1X’s NEO, we are moving closer to a reality in which humanoid robots co-exist with humans in highly unstructured environments. This is a sharp shift from their traditional deployment in controlled settings such as factories and warehouses.

While this transition is exciting, it also brings safety to the forefront, a challenge that is both complex and often underestimated. Large, rigid machines operating near people pose real risks if something goes wrong. Even today’s most advanced humanoids still struggle to reliably detect and navigate around humans in crowded, dynamic spaces.

Startups like Waveye are tackling this problem by treating perception itself as a safety layer. By combining vision with radar based sensing, their systems provide spatio-temporal awareness that goes beyond what two dimensional cameras alone can offer. This allows robots to more reliably detect people, pets, obstacles, and even other robots.

But safety does not stop at perception. A robot’s physical design, including its shape, structure, and materials, plays an equally important role. 1X’s NEO’s body is wrapped in a flexible three dimensional lattice that functions as a soft outer shell, reducing the risk of injury during close human interaction.

This is where material science quietly becomes critical. Advanced materials enable robots to remain lightweight, energy efficient, and compliant with safety standards required for homes and workplaces. While AI determines how a humanoid thinks and decides, material science defines its physical presence and ultimately whether it can operate safely alongside people.

Final Thoughts

Taken together, these trends point to a clear shift in how robotics is being built and evaluated. Progress is no longer driven by any single breakthrough in AI, hardware, or simulation, but by how well these components work together as an integrated system. The robots which are gaining traction are the ones that move reliably, learn efficiently, and operate safely in human environments. As we move into 2026, the question is no longer whether humanoid robots are technically possible, but whether they can deliver real utility at scale. The winners will be those who treat robotics not as a science experiment, but as infrastructure which is built to function quietly, safely, and at scale in the real world.

.svg)